Portrait of a Typical Cell Phone Policy

So you want to know what it feels like to be a teacher these days? It starts with a facepalm. Followed by facepalm. And then, a facepalm.

I work at a high-performing public school in an average school district in a state that’s always in the bottom half in terms of public education (according to U.S. News & World Report, whose rankings are known to be super-sketch) or in a race to reach #50, according to other sources.

All that is to say that North Carolina is not a progressive state regarding public education, and we’re an average district in that below-average state. Set expectations accordingly.

As you may have read (part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4), I’ve covered my push to get my school to go phone-free in some detail. The overall response was a revision of the district’s cell phone policy. I may have played some role in getting this moving (there is a reference in the introduction to the Surgeon General’s 2023 Advisory, which was in the folder I shared with everyone I spoke to).

Still, I had no input on the policy other than any other rank-and-file teacher in the district, other than to fill out the Survey Monkey survey. No one on the policy committee contacted me. According to a newspaper report, 1,398 staff members responded. I was one of those.

I don’t know if any teachers (students or parents, either) serve on the policy committee.

From the brief look at what I’d seen by the end of the school year, there was very little daylight between what we had and what we were changing to.

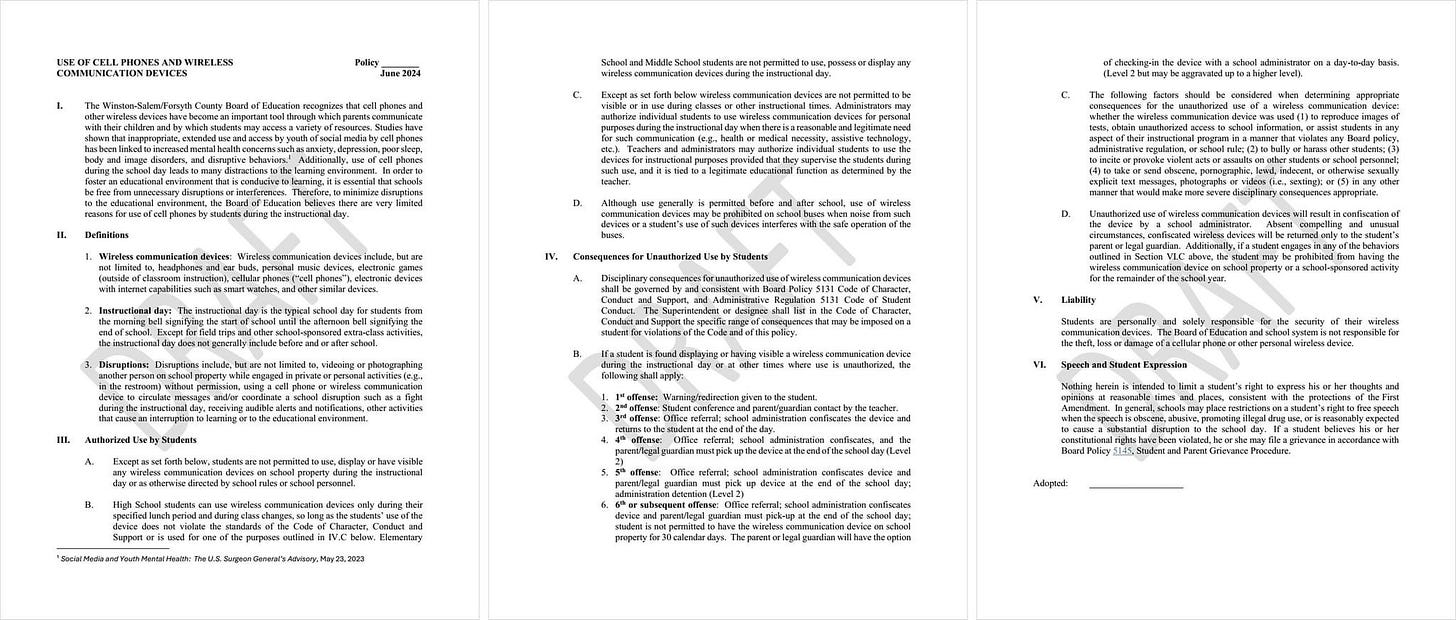

Its full version is out now, and the initial view is pretty much true, but frustrating stuff was added. Here you go—these were made public earlier and are easily accessible on the district website or via social media.1

Anything in black font is unchanged. Green indicates revised passages, and red indicates new passages. The working document is on top, and the final draft is below.

In Short…

I’m not going to go all point by point and write as much as I did last time (you’re welcome), but I do want to make sure we see the major points.

In all of this, try as much as you can to put yourself in the shoes of a public school teacher and make this work in your view of public schools. Again, I work at a high-performing school, so my views are different than those from ten years ago when I worked in a Title 1 school with a pretty rough-and-tumble reputation.

Okay, let's take this thing apart. Again, I see this as a generic “cell phone policy” with nothing unique to my district. If you told me this policy was pulled from an ALEC-style database of cell phone policies, I’d believe you 100%.

I’m skipping part I of the policy. That’s some edgy, irony-based humor I don’t get; It reads like, ”There’s growing evidence that phones are bad, but here’s how we’re going to allow you to keep using them while you’re under our care.” Anyway...part II and beyond.

Students cannot use or have cell phones out during the instructional day, and high school students can use their phones between classes and during lunch.

Sigh—already giving up ground for class change and during lunch. Creepy, dystopian, silent-ish lunches will continue as students stare into screens at lunch and not be social with one another or…be kids. And zombies in the halls. Cool.

Use your phones, kids. That’s what we’re endorsing from the top down, even though part I explains the growing evidence that phone use can be harmful to teens and is a distraction in an academic setting.

Phones cannot be seen in the classroom, so they must remain in a pocket or a bag during class.

Or, in all honesty, in a place where the teacher cannot see it, but the student can still see and use it. See? Putting yourself into the role of a teacher is pretty easy. You already were saying that in your head. I didn’t need to write it.

But the thing here is that this policy revolves around the idea that kids will voluntarily put their phones away. Their phones—the devices that hold an entire world created and curated for them, a device they’re addicted to by its (and the apps on it) design—the kids are suddenly just not going to look at or be interested in them.

Any education policy that depends on kids not acting like kids is bound to fail. Why can people not understand this?

“Administrators may authorize individual students to use wireless communication devices for personal purposes during the instructional day when there is reasonable and legitimate need for such communication (e.g., health or medical necessity, assistive technology, etc.)

Okay—that’s expected and carries over from the previous version. Blood glucose monitors are wireless, and students can monitor them via apps. It’s pretty wordy, probably because no one wanted to touch it after the lawyer wrote it.

Teachers can have students use phones for instructional purposes as long as they are supervised.

I agree and have always pushed for this, no matter the phone solution. Given the glacial pace at which a district moves, keeping scientific equipment updated and current is impossible. However, students' phones have more data collection tools than a box of physics tools from 12 years ago (for example, see Phyphox).

I’m sure there are other uses and apps as well—some will have them film short videos in a (sigh) social media style (ignoring the research about the harms of social media on these same kids) and more. That’s fine, but there should be a high bar and oversight. Does the assignment need to be phone-based? Will that result in the best outcome?

Although using/needing phones for assignments brings equity into the issue, my district has a…collection of definitions of equity, depending on the time, place, and need. It’s odd that the district would write a policy that raises equity questions.

The bulk of the new stuff comes in the form of punishments:

1st offense: a stern talking to

2nd offense: student/teacher conference and parent contact.

3rd offense: office referral, device goes to the office, student can get it at the end of the day

4th offense: same as 3rd, but it’s now a “Level 2” offense.

5th offense: same as 3rd and 4th, but the parent must pick up the phone, and the student gets detention.

6th offense: same as above, but the student cannot have a device on campus for 30 days (although a parent/guardian can check it into the office at the start of the day for the student to pick up at the end of the day).

Of course, depending on what the phone was used for, there are mitigating reasons for upping the punishments. If the student uses the phone for one of the more serious reasons (section VI.C above), they may be forbidden from having the phone on campus (and sporting events—seriously non-instructional time) for the rest of the school year.

But seriously—six offenses? And there’s nothing conclusive there—it honestly feels like they just got tired of writing punishments for offenses after six.

Tell me you’re not taking this seriously without telling me you’re not taking this seriously.

Okay, I’m not going after my district specifically here (again, fingers crossed I don’t get fired)—I see this policy as an average policy that many schools have or will be “implementing” at the start of the coming year across the country. It has no frills or anything that makes it stand out. It’s a cell phone policy boilerplate.

Around the country, the boards and policy committees will congratulate themselves for doing what’s best for kids, they’ll smile for pictures on the district website, and we might get new posters about the policy to put up in our rooms. And aside from the pride the policy committee feels from “doing what’s best for kids”…

…nothing will change.

On Unfunded Mandates…

How are you coming with the “put yourself in the shoes of a public education teacher?” Starting to feel anxious? Frustrated? Have you ever talked to a teacher and asked them what the job is like, and they get a little wistful and weird and say, “It’s…you know…I love the kids.” Which in no way answers your question meaningfully, yet actually does.

Seriously, it’s like this every day.

Completely ignoring the when and when-not; let’s look at the discipline portion again—the new stuff, which makes up about half of this revised policy. You caught that, right? The “revisions” to the policy mostly just lay out punishments.

Play along at home. Here are some thoughts that we’re all having:

Teachers are still the phone police. It’s on us.

I guess teachers should keep a log of student phone offenses that will be documented from the first through the sixth. But come on, if your policy outlines disciplinary steps for six offenses, you’re not dealing with a serious issue—you’re dealing with a nuisance.

What’s “instructional time?” No, seriously—if I have ten free minutes at the end of my class (I shouldn’t, but that’s another thing). Can my class get on their phones?

How do teachers get the phones to the office? My school is freakishly big. It’s about a tenth of a mile to the front office. I plan my days around when I need to go there. Do I hold the phone until my planning period and then take it/them? Will the office have a phone runner (it can’t be a student—liability)?

All teachers will tell you that parents texting/calling students contributes to phone use in class. There’s nothing here that’s going to change that, and the teacher may now have to confront the parent about disrupting the student’s instructional time. That will be fun.

Who’s checking to ensure the student isn’t carrying a cell phone for the 30-day (or longer) period? Students regularly get contraband around the metal detectors—getting a phone past a functionally non-existent checkpoint is a non-issue.

And who in the world is remembering (and checking) which students can’t bring their phones to sporting events? Whaaaa?

I spot a student walking to the bathroom on their cell phone. Does that count? Pee-pee/poo-poo time is not instructional time, after all, and they don’t need to turn it in.

Who’s enforcing this on the buses (see III.D)? Like many districts around the country, we barely have enough bus drivers.

Are the offenses counted in one class or cumulative during the day? Let’s say student X uses a phone in my class (1st period), and I have a stern conversation with them. Then, in the second period, they use it again, and that teacher has a stern conversation with them, right? Let’s say the student does it again and again throughout the day (they are addicted, after all…), and by the end of the day, does that student have one offense in four classes or four offenses, and the phone should be in the office, only to be released to a parent/guardian?

We do have a system where we can write up offenses (Educator’s Handbook), and in theory, this could be done such that by the time of the fourth offense, that fourth-period teacher sees that something is up and writes it up as such. But that would require everyone previous to have the time to write it up in the period (rather than the end of the day, lunch, or planning) and someone to be playing the switchboard and catch the four offenses coming that day and take action.

Oh, and for what day is the phone taken away (we have four 90-minute blocks) if the offense is in 4th period? Is it that day or the next day? The punishment isn’t equitable if a student in first loses their phone for the whole day, while a student in 4th loses their for 30 minutes. It was the same level of offense, after all.Can teachers still collect phones at the start of class like I do? Since that’s not explicitly stated in the revised policy, I figure some teachers will feel that they can’t, while others (like me) will keep doing what they’ve done.

But since the policy says nothing about the teacher having the phone in their possession during class, a sharp student or parent could argue against a teacher collecting phones, and win.What happens if the offense write-up is put together, and I forget to put the new cover on the accompanying TPS report?2

This list is not exhaustive, but I am exhausted thinking about it. There are many more very valid points to be raised.

Are you starting to get a feel for it now? Every day, you have to navigate a path that will (a) educate the kids and (b) not get you into trouble due to something you did, something you forgot to do, or something you weren’t even aware you were supposed to do.

Oh, and all of these points are only if you’ve got one student with their phone in class.

And I guarantee that when admin staff has to discuss a new phone policy like this at a startup meeting, all of these questions (and many more) will be asked. Responses will include (but are not limited to):

A folksy, “Hey, I don’t make the rules, I just do what I’m told” defense (aka, STFU)

“Well, we could have a two-hour meeting about this, but we’ve only got 20 minutes scheduled. Does anyone else want a two-hour meeting?”

Peer pressure—the person wanting clarification will be eye-rolled into silence.

People will get up and leave when the meeting reaches its scheduled ending time.

But some of us do want clarification and want it to make sense in our day-to-day, especially your neurodivergent teachers who need things to make sense3 and teachers who want to do the right thing rather than the wink-wink-nudge-nudge “right thing.”

And being told (in so many words) that your need for wanting things to make sense isn’t important in a meeting with your peers and colleagues really, really sucks4.

Oh, and elephant, room regarding in-classroom phone policing:

ALL OF THIS IS TAKING TIME AWAY FROM TEACHING—THE THING WE WERE HIRED TO DO.

No one gets evaluated on how well they enforced the cell phone policy. If anything, you get evaluated on how your kids do on standardized tests. Any teacher worth their salt will prioritize instruction over playing phone cop.

And in the end…

The success or failure of a plan like this hangs on the weakest link in the chain. If you’ve got a teacher who doesn’t enforce the new policy for whatever reason, it’s done. You might as well not enforce it.

And there will be5:

teachers who will look the other way for some kids and let them step out in the hall to talk to a parent because they’re upset,

teachers who are scared of getting into confrontations with the particular students using their phones (or their parents),

teachers who refuse to yield authority in their classroom to a new “policy” when what they have works better,

teachers who went to the meetings but yet have their interpretation of the policy and enforce it as they see fit,

teachers who are just exhausted and can’t keep up with one more thing on their plates,

substitute teachers,

teachers (and perhaps schools) who will not explain this new expectation to students and parents.

There will be administrators who forget6 to discuss the new policy with faculty at the start of the year. Don’t worry, though—many administrations will explain it to teachers at the start of the year. However, many teachers will be on their phones during the meetings and may not catch the nuances.

And none of this takes into account the October Forgetting7. New teachers positively clench up into little balls of anxiety and stress at the start of the new school year when they hear about all the new policies, initiatives, in-classroom visits, and goals the school has for the coming year.

Veteran teachers find the panic-breathing baby teachers who are freaking out, shush them and take them under our wing. “It’s okay,” we tell them, “By the time October rolls around, they’ll have forgotten about 80% of those things, and you won’t hear them mentioned again.”

Sorry, administrators who are reading this, but you know it, and we know it. Plans are terrific things to have.

If you want to make the universe laugh at you.

Sigh.

I’m tired of talking about phones—seriously tired. But this is what not talking enough, not talking loudly enough, not talking to enough of the right people, and not getting in enough good trouble gets you: a revised policy.

A revised policy that was written by functionally (and maybe literally) the same people who wrote the policy that got us here in the first place.

This was a massive opportunity and will be a massive unforced error for many districts and schools. Like many other schools in the state and country, we could have been phone-free this coming year.

Instead, we’re still phone-based.

Again, this piece, which uses my district’s revised policy as an example, is not meant to slam my district. I’m holding this policy up as a nothingburger in public education and cell phones. It’s an average policy—interchangeable with one in Any District in Anytown, USA.

Okay, that was a joke. I think.

Yep, it’s me. Hi. Proudly ADHD and ASD, masked during the day and exhausted every evening from pretending to be a normie. I do not understand how y’all do it.

Personal experience.

Every teacher has examples of teachers who have done or do things like this. If they say they don’t, then they’re the ones doing them.

Accidentally or on purpose.

Remember the year before last, when we were all worried about burnout? There were signs to watch for, methods for overcoming burnout, “Remember to practice self-care!” in admin email signature files, and so on. Did anyone mention burnout at your school last year? Any sig files still advising to practice self-care? Are teachers no longer burned out, or have we just stopped talking about it?