Earn the Seat: What a School Board Is — and Why Mine Failed

A crowded primary, a failed school board, and the bare minimum standard for governing public schools.

#local

My district dug itself into a $46 million hole.

The board couldn’t even elect its own leadership during a crisis.

And now it’s primary season, and everyone suddenly wants to “serve.”

Let’s reset the baseline.

Somewhere along the line, school boards stopped being boring governing bodies and started becoming audition spaces — high-stakes positions filled by people who too often don’t understand the job they’re supposed to do.

The result is as predictable as it is preventable: the people paying the price are the ones inside the buildings.

And now, the yard signs are blooming. The mailers are coming. Everyone has a slogan.

Before we hand over the gavel again, let’s define the job.

What a School Board Actually Is

A school board has a small number of jobs:

Hire and evaluate a superintendent.

Approve and monitor a budget.

Set policy.

Oversee internal controls, contracts, and facilities.

Protect the district’s long-term stability.

That’s it.

It’s not glamorous work. It’s not loud work. It’s disciplined, procedural, and detail-heavy work.

A functional board spends more time in spreadsheets than in speeches. More time asking follow-up questions than delivering monologues. More time building majorities than building personal brands.

If that sounds dull, good. Governance is supposed to be dull.

What It Has Become

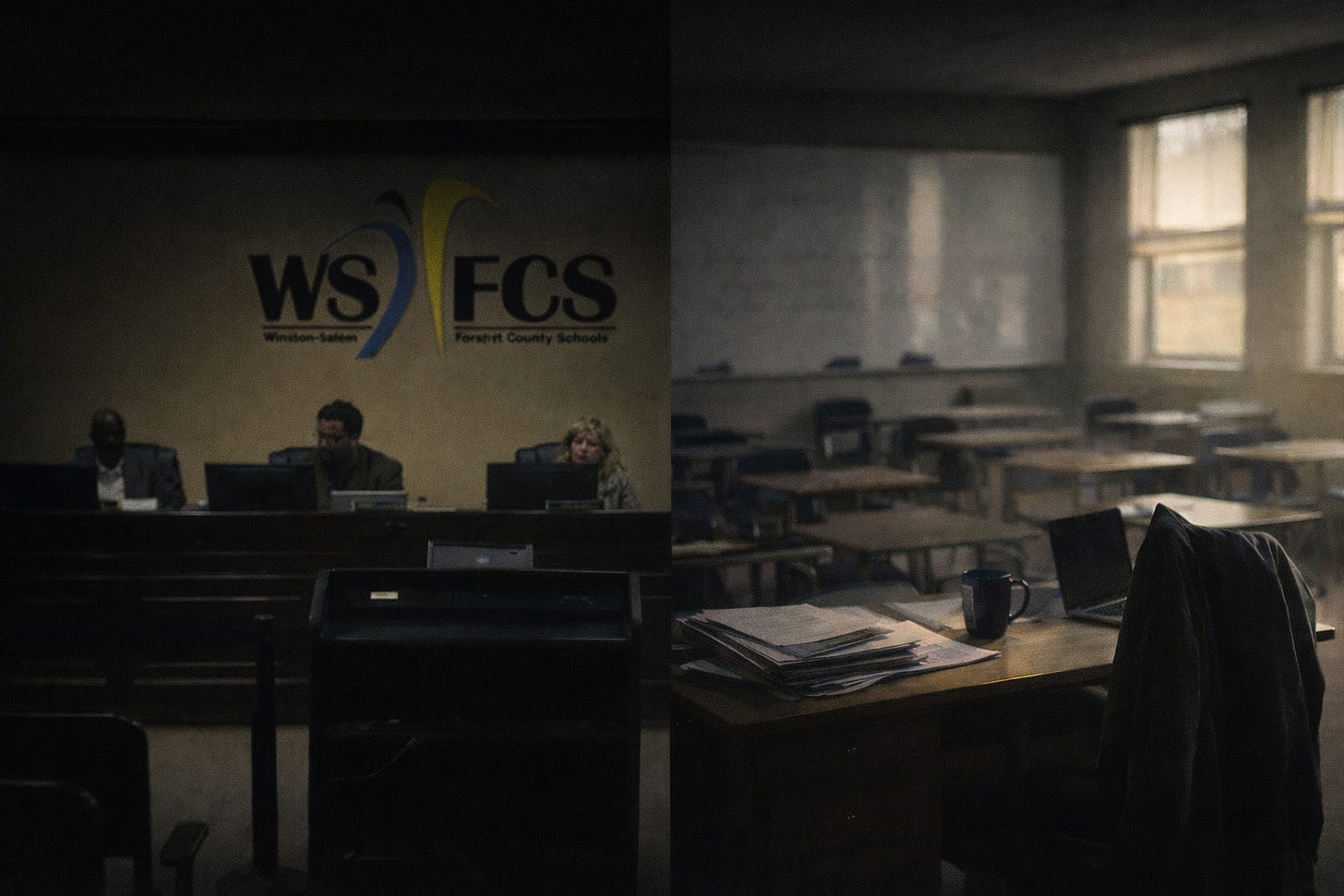

I’ve seen it in my own district. We’ve watched a board struggle to elect its own leadership during a financial crisis, multiple rounds of voting. No resolution. Public stalemate.

At the same time, the district was facing the fallout from a state audit that detailed years of financial mismanagement, including a roughly $46 million deficit, repeated budget overrides, weak internal controls, and failure to align staffing with enrollment declines.

That is not a blip, an oops, or a “how did this happen?”

That is a governance failure.

To the district’s credit, WS/FCS has publicly acknowledged the crisis and outlined steps toward financial correction and increased transparency. and that matters.

But acknowledgment after the fact does not erase years of oversight failure. A corrective plan is necessary — it is not exculpatory. Recovery is not the same thing as competence. To date, no one at the governance level (board or upper district management) has been held accountable for failing to govern. Meanwhile, we’re all being asked what the district can do to regain the trust of the community and staff.

Now let’s widen the lens.

A school board is not a minor league for aspiring politicians. It is not a launchpad. It is not a place to rehearse culture-war talking points until someone hands you a bigger microphone.

I am sick of watching people treat the management of public education like a branding opportunity or a hobby.

This job is supposed to be about budgets, policies, oversight, and the unglamorous work of making sure the lights stay on and the teachers and staff get paid. Instead, we get mismanagement. We get theater. We get rehearsed indignation. We get vague conspiracies whispered just loudly enough by self-proclaimed “heroes.” We get shock that district staff and the public would dare question the board’s actions and inactions —or ask for accountability.

And here’s the part that should make everyone uncomfortable: Every minute spent posturing is a minute not spent governing. Every viral clip is a reminder that the person speaking into the mic might be thinking about their next campaign instead of this district’s current crisis.

If your goal is to build a personal brand, go start a podcast. Go run for Congress. Go get a ring light and argue with strangers online.

Do not use 50,000 students and thousands of employees as your political internship.

Meanwhile, teachers are trying to teach. Students are trying to learn. Families are trying to trust that someone in the room is an adult.

Instead, we get spectacle — and leadership that hasn’t earned the name.

And the quiet damage — the erosion of trust, the normalization of dysfunction, the steady drain on morale — spreads far beyond one meeting, one vote, one viral moment.

Something has gone very wrong.

So Who Should School Board?

A primary is coming — March 3, 2026 — and the field is crowded. At least 37 candidates have filed to compete for nine seats on our board. Incumbents. Challengers. Fresh faces. Familiar names. All are asking voters for the authority to run this district.

Like modern politics everywhere, an election appears, and suddenly everyone wants to “serve.”

Good.

Democracy requires choices.

That’s one victory for the current school board - they did mobilize a large field of candidates who all want to take their jobs.

But let’s talk about how people tend to vote in these races — and why that’s part of the problem.

Too often, we vote for:

The person with our party label.

The person from our church.

The incumbent recasting themselves as the isolated truth-teller — long on retrospective explanations, short on contemporaneous receipts.

The person we recognize from a yard sign five years ago.

The long-serving incumbent who believes that “experience matters.”

The loudest candidate, because at least they “fight.”

That’s not school boarding.

That’s brand shopping.

To school board — yes, I’m using it as a verb — means something different.

It means walking into the room already understanding the job.

Not “excited to learn.”

Not “bringing fresh energy.”

Not “figuring it out as we go.”

We have already lived through what happens when people learn on the fly while sitting on the board. A significant part of how we got here is that too many people on this board did not understand their responsibility. As a result, state-level bodies moved to require external reviews and additional audit work due to the crisis.

Governance is not vibes.

It’s not instinct or being led by your gut.

It’s not “asking good questions” while the numbers burn.

It is oversight. It is fiduciary responsibility. It is systems-level thinking.

And when you don’t understand that — when you treat a multimillion-dollar public institution like a discussion forum instead of a governed entity — you get years of budget overrides, weak internal controls, and crises that “suddenly” appear even though the warning signs were documented.

That is not bad luck.

That is a failure of understanding.

To school board means you can:

Read a 200-page budget and grasp its meanings and implications — and spot problems.

Understand enrollment trends and staffing ratios, both now and in the future.

Ask what internal controls exist — and what happens when they fail.

Know the difference between governance and administration.

Vote in a way that protects long-term stability instead of short-term applause.

This is not an entry-level position. It is not student government, a church board of deacons, an internship, or a leadership workshop that’s a step towards something bigger in the future.

It is fiduciary oversight of a multimillion-dollar public institution that employs thousands of people and educates tens of thousands of children.

You do not show up “ready to learn,” you show up ready to govern.

And let’s be honest: there are candidates in this race for whom this job may simply be too much.

Too much complexity.

Too much financial responsibility.

Too much need for restraint.

Too much consequence.

That’s reality. Despite the good vibes on social media and well-wishers at election meetings, not everyone is built to govern at this scale.

And especially now — after documented oversight failures and public dysfunction — this district cannot afford another round of well-meaning amateurs.

Not another long-building “surprise.”

Not another round of layoffs followed by platitudes.

Not another “how could this happen?”

Institutions don’t collapse in a single dramatic moment. They erode.

And we are eroding. The budget and staff cuts didn’t cut the fat in the district. There’s no fat left. They cut muscle. Ask teachers and administrators, and you’ll hear one phrase: “not sustainable.”

We cannot survive another round of this. Not another ‘how did we miss it?’ Not another mass cut. Not another year of ‘trust us’ after the fact. If we keep electing people who don’t understand the job, this district will hollow out and be done.

Competence is not elitism; it’s the minimum requirement.

Here’s another uncomfortable lens through which to view the contenders: the stake.

Who actually has a stake in the outcome?

Do they have children in the system?

Have they worked inside public schools?

Have they demonstrated long-term investment in this district beyond election cycles?

Will they personally feel the consequences of instability?

Because we’ve just lived through hundreds of jobs cut, careers disrupted, families uprooted. And for too many decision-makers, it cost nothing.

No classroom lost.

No careers upended as they were starting.

No paycheck vanished or decreased by months’ worth of money.

No daily disruption at home.

No emotional stress.

Just carefully measured “sympathy” that cost nothing.

When you have no skin in the game, governance becomes abstract. Numbers on a slide. Positions on a spreadsheet. But for the rest of us, those numbers are colleagues. Friends. Mentors. People who built lives here.

So as this primary approaches, ask better questions.

Don’t ask who sounds strong.

Ask who can govern.

Don’t ask who fights hardest.

Ask who can collaborate.

Don’t ask who shares your party.

Ask who understands fiduciary responsibility.

Don’t ask who shares your beliefs.

Ask who understands the job.

Don’t ask who goes to your church.

Ask who has skin in the game.

That’s how you school board.

This is not revenge politics.

This is performance review.

If you are currently serving, your record is the résumé. Not your intentions. Not your explanations after the fact. Your record.

If you were in the room while oversight failed, while leadership collapsed into stalemate, while dysfunction became normalized — you don’t get to run again as if you were a bystander or an outsider. Governance is collective. So is accountability. Own it.

Continuity is only valuable if it is continuity of competence.

And if you are running — new face, fresh slogan, polished mailer — understand something clearly:

This seat is not a stepping stone.

It is not a personality platform.

It is not a culture-war trench.

It is not a place to grow a following.

If you are more excited about being quoted than being effective, don’t run.

If you are more fluent in outrage than in oversight, this may not be the seat for you.

If you think “strong leadership” means dominating a microphone and scoring “points” instead of building a majority, leave it to someone else.

If you cannot sit at a table with people you dislike and still govern responsibly, absolutely do not run.

We need adults.

Adults who read the audit.

Adults who understand fiduciary responsibility.

Adults who know the difference between attention and achievement.

Adults who care more about institutional stability than personal advancement.

No one is owed this seat.

Not because you’ve been there before.

Not because you “care deeply.”

Not because you have the loudest supporters.

You earn it — or you don’t.

The rest of us have been doing our jobs under the weight of decisions we didn’t make. We’ve absorbed the chaos. We’ve explained it to students. We’ve reassured families about district and staff stability, often when we didn’t believe our own words. We’ve kept the classrooms steady while governance wobbled.

We’ve watched staffing shuffles that seemed to be made with incantations and dice. We’ve given long hugs, said goodbyes, tipped back beers, and wiped away tears as old colleagues and kids new to the job were told that, through no fault of their own, they no longer had positions.

That grace period is over.

If you want to lead, prove you can govern.

If you can’t, step aside.

Public education is not your audition.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here are my own as a classroom teacher. All factual references are based on publicly available reporting and official audit documents linked in this article.