A preface—this is the one I didn’t want to write. In a push to make classrooms and schools phone-free, student safety during a shooting is the thing you want to talk about the least. When phone-free efforts are mentioned, the mention of safety immediately disrupts threads on social media and rightly strikes a nerve with parents.

I didn’t want to write about this, but I had to.

And I don’t have an answer. I’m a parent (mine’s graduated and out, but still a recent product of public education), so I can walk that line. But I also know the benefits of going phone-free. It’s a tough spot to be in.

I don’t have the answer, but I know there must be a conversation. I wanted to provide as much background and context as possible.

Also, before I get going with this, I want to explain a thing: Given the world in which we live and work, a teacher’s (mine) sense of humor may be slightly…off compared to yours. I mean no disrespect.

And I will tell you from the start that this topic is difficult for teachers to speak about dispassionately, so there may be cursing. Aside from police, soldiers, and the cast of Heat, I’m not sure there are many other jobs where you have to come to an understanding that on any given day, you may meet your end in gunfire.

Yay, teaching.

The Message is Coming From Inside the School

I’m not in some tower or office, suggesting ideas and making decrees where I have no personal stake. I’m in a classroom at a high-achieving high school. There have been shootings at other schools in my district, and not to go all Government Accountability Office on it, my school checks a lot of the boxes for a shooting.

Teachers feel that it’s more an issue of “when” not “if” there will be a shooting in our school. We know the most vulnerable locations and times for a motivated shooter. We don’t advertise them, but we know them.

We roll our eyes and look at each other in meetings when we get the “new” plan for school safety. We sigh at the previous plan’s guidance (“drop the curtain down to block the door window,” or “slide the red card out into the hallway if someone in your room is injured, and the green card if everyone is okay.”) is replaced (“there should be no curtains on the doors in the case of an emergency” and “who said slide cards out into the hallway? We never said you should slide cards out into the hallway.”)

We chuckle darkly (inside, not out loud) as our kids point out the considerable weaknesses in the school’s safety plans. And we wonder why we’re asked to blockade a classroom door that opens into the hall.

As a chemistry teacher (and again, this is under the umbrella of dark humor), if the day comes when an active shooter roams the halls of my school, my kids know that we go in and huddle in the chemistry supply room. It’s two locked doors away from my classroom door and pitch dark.

In my darkest moments, I know that if that unthinkable happens, I’ll take the 12M hydrochloric acid off the shelf. If that door opens, I aim for the face.

If they open that door, their bad day will end very painfully. And no open casket funeral.

I’m not flexing. Every teacher you know has had versions of thoughts like that. And some even have thoughts along more fatalistic lines. We’re only a few more shootings until, as part of beginning teacher training, you have to have a course on end-of-life plans.

And every teacher you know will lay down their lives to protect the children in their care.

I hate, from all that I am, that I have to even let these thoughts into my head. But this is where we are.

Keeping the Real Talk Going

While we’re talking about school shootings, let’s rip that whole Band-Aid off and go for it.

I’m not going to make this about gun control, but as a society, we refuse to do anything about access to guns (or mental health spending). As a result, we’re left with one option—harden the targets1. All we can do within this defeatist mindset is make it harder for those who wish to cause harm to do so.

Schools added School Resource Offices en masse in the late 1990s (Columbine was April 20th, 1999). However, the result of the money spent and other unintended consequences of SROs has been, at best, mixed. We’ve welcomed sworn police officers into public schools, but we still have school shootings. This feels like a case of “if it were going to work, it would have worked by now.”

Even though we have SROs (to the detriment of some students), students, teachers, and parents have no guarantee that they won’t Uvalde or Parkland out on a school when the

unthinkablepreventable happens and act like this when it comes to who’s going to nut up and do their damn job:

Claims by felons notwithstanding

While talking about SROs, ours bounce back and forth between the city police and the county sheriff deputies, depending on which group gives us the best price.

We move back and forth between school safety programs, not based on research and effectiveness, but on which free one looks best or who gives us the best price among the paid options (free options are the rough equivalent of “thoughts and prayers,” while paid options have bells as whistles and a “system”).2

And schools themselves…look, no administrator or teacher wants to ever be in a situation where a school shooting happens. No one gets into education for that. But, as most parents and teachers know, clear communication is often not the top priority when a school emergency requires a lockdown.

Perhaps it's a side effect of changing safety programs or just plain old archaic policy, but keeping teachers or parents in the dark cannot happen. Every teacher you know has had a lockdown in their school, and they didn’t learn the reason until the end of the day, or they are still wondering about it.O.G. school shooting training programs used to be about waiting—11-15 minutes (or less). That’s how long a typical shooting lasted, and police were in the door. Just run down the clock. Those were the old days. The latest school safety training acknowledges or expects that you (or your kids, in a “swarm”) will fight for your life against an assailant.

All honesty? That was always in the back of our minds (see above), but now we say it out loud as part of training? Jesus.Active shooter drills are some of the shittiest times you can have as a teacher, and there’s growing evidence that, like metal detectors, they make schools a place where kids don’t want to be. And that’s not even getting into the active shooter drills with police officers or other “shooters” firing airsoft guns at teachers.

Arming teachers? That’s a non—starter for me and probably something I’ll write about later. But just in a quick look, there are around 30 states allowing teachers to carry on school grounds. Again, we’ve decided that we’re not going to do anything about the problem, and in return, we just need to add more guns to the mix.

Every teacher thinks about a school shooting. Every teacher has a plan; every teacher has nightmares. Every teacher knows the school’s weak points and hopes that that kid who looks weird and angry doesn’t think too much about them.

It’s almost as if thoughts and prayers aren’t working.

But, the thing is, all of the above are just systematic bullshit, and none of them are fixed or work better if students have phones in the classroom.

Let’s try to lower the temperature here.

Deez Data Points

These are all presented with the understanding that one student murdered by a shooter in a school is too many. That said…

Guns are the leading cause of death of teenagers and kids, but school shootings that result in death are rare on a per-student basis, with the majority of them not being indiscriminate shootings. Over the past twenty years, there’s been one indiscriminate shooting per 130,000 schools.3 Most shootings of kids are accidental or the result of other issues between individuals. One study puts the odds of being killed in a school shooting at one in 614 million. Driving (or riding) to school is far more dangerous.

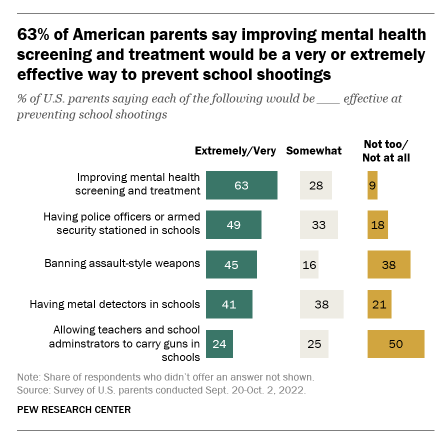

School shootings can be prevented as long as the signs are known and there is a program for interventions. This is the mental health aspect of it we’ve decided not to spend money on, despite lots of people wanting to and research saying it works…

Again, the vast majority of students killed in school shootings are not shot in random attacks. Most school shootings occur outside, after school (all that money spent for security inside the school…$hame), or in the morning as the result of a beef between students.

School safety policy is being built on fear rather than facts, which amplifies the worst aspects to the point that you can’t help but think this happens to every school every day. It's worse when politicians realize that school shootings are a horse that can carry them across the finish line in election years.

Media reporting on school shootings is produced to attract eyeballs and clicks and is mildly to wildly sensationalized (and possibly imitated as a result), resulting in an outside feeling of danger and threat among parents, students, and teachers. That fact up there that most shootings happen outside of schools as a result of personal disagreements? Yeah - when you think of “school shootings,” you’re not thinking about that type, necessarily, are you?

The lens through which parents see their child’s safety needs context. As Jonathan Haidt and Jean Twenge write, as a generation, we have become convinced that a sexual predator or murderer is around every corner and that our children are under constant threat. We share the nickname “The Anxious Generation” with our kids.

As a result, we overprotect them in the real world (while underprotecting them in the online world). The irony is that we were allowed to run free independently or with friends as kids. Now, we shelter our children in ways our parents never sheltered us and demand 24/7 contact. The quick “where are you” contact we want with kids today would have caused all of our stories of rebellion to be featured on After School Specials if we had it when we were kids.

Crime rates are reaching for historic lows, yet fears about personal safety and perceptions of crime are at near-record highs.

Pew, “What the data says about crime in the U.S.” Maybe it’s not just students who should go phone-free… I’m not expecting to change minds by quoting statistics, but our lenses tend to get dirty, thanks to the yuck we spend our time looking at.

Or, as an inevitable pop culture reference…

“We all see what we want to see. Coffey looks, and he sees Russians. He sees hate and fear. You have to look with better eyes than that.”

- Mary Elisabeth Mastrontonio as Lindsey Brigman, The Abyss

Student Phones During a Shooting

Again, if the preventable tragedy of a school shooting happens, phones generally aren’t the help parents think they are. The points:

As I was told by a school security expert, in an emergency, first responders need to be able to communicate and call for backup and medical assistance. A large volume of calls, all using the cell phone relay nearest the school, could jam it up, making outgoing and incoming calls impossible.

Calls made by students to panicked parents could cause the parents to drive to the school en masse, swamping the roads and approaches—paths needed by the first responders or otherwise being kept clear for tactical purposes.

Students need to remain silent during a lockdown situation. An alert or ringtone on a phone can put that student and others in danger. Also, a lit-up screen in an otherwise darkened room has the same effect.

Students trying to learn more about what’s going on from friends or social media pull attention away from listening to instructions. The same applies to students who post on social media during an emergency.

Access to phones increases the likelihood of rumors and misinformation spreading about the emergency, blowing minor incidents out of proportion, further panicking parents, and hampering emergency workers. Not to mention, social media posts would be picked up by local media (“Can we film the operation? Is the head dead yet?…Get the widow on the set!”) as they casually toss gasoline on the fire, praying for higher ratings.

The call phone call volume could easily jam 911 switchboards.4

Crisis response teams need one narrative sent to parents during an emergency, not 100, each turning emergency information into a literal telephone game. Which would go to the media.

If the shooter is on social media during the shooting, posts from students can provide location information, as well as inform them about police response and actions. If the shooter is a student and their identity is still unknown, they could lure other students out via text for help.

Phones or devices using the school’s Wi-Fi could overwhelm the system at hte various hotspots, slowing or jamming camera feeds and other communication.

Other Ways Phones Make Schools Less Safe

It’s not all about the shootings.

I’ve seen fights start in a school cafeteria as students check their phones to see what another student has said about them. That was back in the day—now, it would be called cyberbullying. Word of an impending fight can spread like wildfire through group chats.

I’ve also seen phones used to blow up small or nonexistent events into school-emptying events. When a parent comes to your school enraged that they haven’t been notified of a threat their student told them about, there’s not much you can do except let the student go.

There have been cases of students using cell phones to call in bomb threats as well as cause other disruptions. Phones play a key role in inappropriate videos and photos being taken of students—often used for exploitation, sextortion, or worse.

Drugs are easily accessible through dealers who haunt Snapchat (which aids and abets them, thanks to Snap’s built-in features) along with other social media platforms. If you have a teenager on social media, they know how to find drugs. Check your phone during lunch, and figure out what bathroom and when you need to check out to grab a vape (at best).

And that’s not even getting into the effects of phones (and their attached social media) on student mental health, which is its own thing.

I find it strange that, as a school, we’re charged with doing what’s best for these students in the same way their parents would (in loco parents, yo), but we end up allowing students to do or have access to harmful things.

But…

There’s always a but. Phones are the best way to use “Say Something” programs like the Sandy Hook Promise’s system—they offer anonymity and real-time responses. But^2, tiplines carry the potential of everyone being seen as a potential informant, which is a pretty lousy space to live in, but again—here we are.

Update (8/7): When I ran the above past one of our school counselors, she quickly pointed out that the “Say Something” program is on our school’s homepage, and all incoming freshmen are told about it. So it’s not a phone-exclusive thing.

Schools don’t always have a reliable or functioning crisis communication policy or team. As a parent one bad experience with a school’s “emergency communication system” could easily be enough for a parent to say to their student, “Don’t you worry about what the rules are; I want you to have this phone on you all the time.”

As mentioned earlier, this sometimes leaves parents (and teachers) wondering what’s happening at the school. That has to change. The National School Safety and Security Services website has good guidelines for any school to improve communication during an emergency.

Some schools have this down, and others must completely overhaul and rebuild their systems.

Trust and communication are the keys.

Statistics aren’t.

Vein-popping, vocal cord-straining shouting matches aren’t either.

Oh, and impassioned opinion pieces about how “If we can't get gun control, then the kids should get to keep their phones on them,” and letters to the editor saying we can, “Ban phones after the school shootings stop,” aren’t helping either.

C’mon.

In the End…

One student killed by a school shooting is too many.

This wickedly complicated topic requires thought, empathy, and conversation, not jamming a policy down the throats of a group that feels like they’ve had no say in it. Unfortunately, public education tends to be good at the latter, not the former.

I’m torn by this issue in my push to get schools to go phone-free. This is where I can potentially break with anyone who’s marching to the drumbeat of phone-free schools who’s not in the classroom. Principal Ewell Fuller of Stanhope Elmore High School in Millbrook, Alabama, explained a workaround to me.

He adopted Yondr pouches, allowing students to carry their phones in the locked pouches during the day. The first week after they started using them, Stanhope had a lockdown. Per policy, students could access their phones following the lockdown's clearance. The Assistant Principals and select teachers had the magnetized unlocking bases, and Fuller explained that they could have the entire school’s phones unlocked within ten minutes.

That approach makes sense to me, and I’m completely sympathetic to letting students communicate with parents once the lockdown is cleared. I don’t know how to make that all work with different phone-free approaches.

I am certain that the potential benefits of phone-free schools outweigh the drawbacks. The benefits to students of not accessing their phones during the day are greater than letting them have unhindered access to them “just in case of” an emergency, in which the use of a phone won’t help them and which the vast majority of schools never see during the school year.

Luck to all of those who are going to be walking down this road in a push to go phone-free.

To which, those who $ell “target-hardening” gear are eternally grateful.

Caught that theme, did you? Student safety is in the hands of woefully underpaid teachers and the lowest bidders.

I fully, fully understand that this is cold comfort. I had a kid go through public school, and I thought about school shootings a lot as well. Statistics aren’t worth a crap when it comes to my kid. I get it. I’m just trying to find a path forward.

Yes, students in Uvalde did call 911 while the shooter was still in the school (and classroom), but everything went wrong in Uvalde, and it can be argued that if the responders had done their jobs, the call would have never had to have been made.